Can body language really affect election results?

When people assess politicians in the media, physicality and body language have a significant, albeit subtle effect. It’s said they can swing a close-call election, although this is controversial.

The claim arises from the very first televised leadership debate, which took place in the US in September 1960. Around 70 million viewers watched as vice President Richard Nixon was pitted head-to-head against the young, relatively inexperienced senator, John F Kennedy.

Despite his vast political experience, Nixon did not come across well to the viewing public. He had been in hospital for two weeks in August 1960, with an infection that left him sallow, drained, and twenty pounds lighter in weight. On the day of the debate, he was at the end of a bout of flu, with a raised temperature, and had banged his bad knee getting out of the car at the TV studio. By the time the cameras started rolling he was grey, in pain, and no match for the handsome, charismatic, tanned JFK.

Lessons in political body language

As well as the differing appearances of the two Presidential candidates, their body language was worlds apart. JFK looked into the camera to answer each question. To viewers at home it seemed as if he was addressing them directly. Nixon, on the other hand, spoke both to the reporters in the room and to the viewing public, not realising that moving his eye-line to do so made him appear shifty.

While radio listeners were convinced by Nixon’s political arguments and felt he had won the debate, TV viewers were convinced by Kennedy’s physicality.

At least that’s how the story goes. The evidence for this seems to have been lost in the mists of time, although some people believe it was based on a survey of just 2,100 people, of whom just 13% listened on radio, most of them Republican (Nixon) supporters. So it may or may not have its basis in truth.

Either way, just a few weeks after the debate, Kennedy won by a tight margin.

The rocky politics show

As the UK’s general election looms, many Brits are caught between what they see as a rock and a hard place. Jeremy Corbyn is widely disliked – even among ardent Labour supporters. Theresa May is leading Brexit – the blight of many people’s lives.

On 8th June one of them will be elected Prime Minister. But who will people vote for? And how might the body language of these two would-be leaders make a difference to that decision?

This week Mrs May and Mr Corbyn appeared on TV, answering audience questions before being grilled by the UK’s most feared, intimidating interviewer, Jeremy Paxman. Although this wasn’t quite a debate, as they weren’t in the studio at the same time, there is general consensus that there was no clear winner.

So what feelings did the ‘debate-that-wasn’t-a-debate’ trigger in people’s subconscious, particularly in relation to body language?

It’s just a jump to the left….

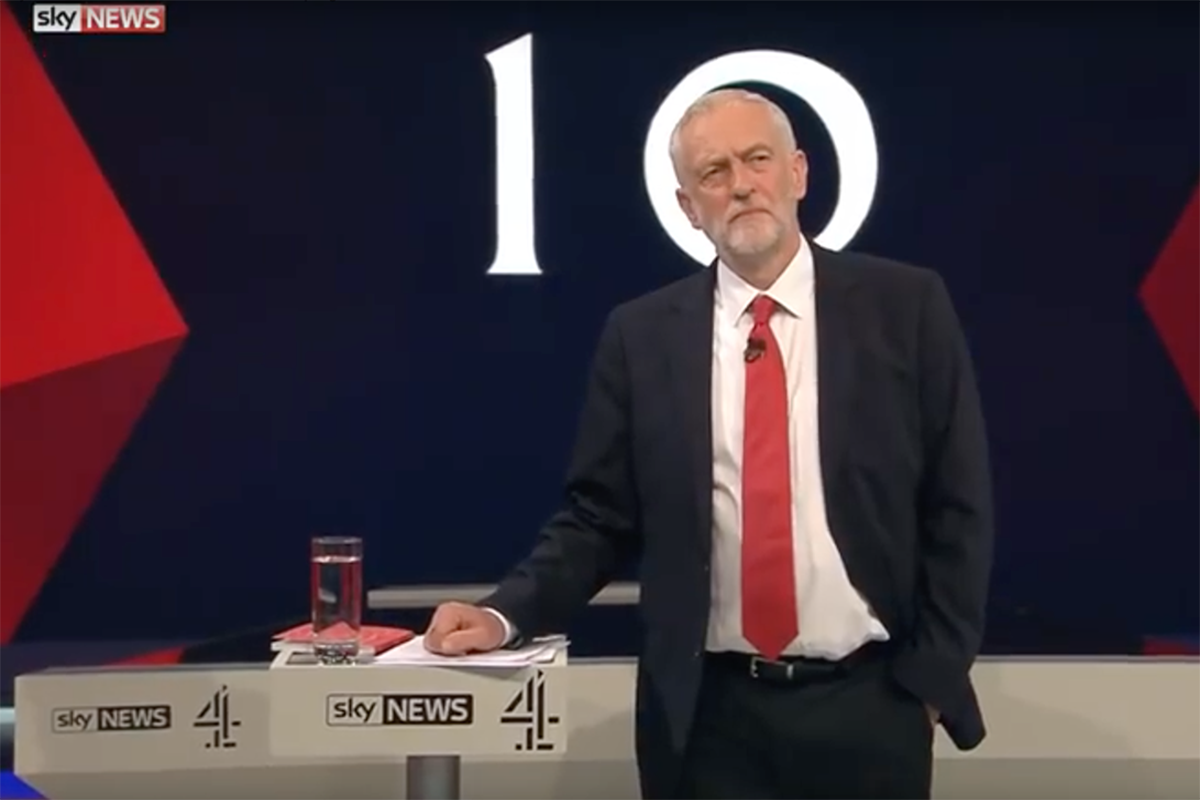

Let’s consider Jeremy Corbyn to start with. When he came on stage, he couldn’t work out whether to be ‘bloke in a bar’ (aka Nigel Farage) or ‘serious leader’ (aka David Cameron). He stood with hand in pocket, leaning on the podium with one hand, weight on one foot, for all the world like he was just about to order a pint of beer.

He must have realised this wasn’t exactly professional, for he quickly changed into salesman mode, emulating the powerful, hands-open gestures of his Labour forerunner, Tony Blair. At this point he came across much more professionally – although he still lacked gravitas.

This was partly because of nerves. The earnest looking Mr Corbyn fiddled with his fingers as though reassuring himself. This type of gesture emulates a parent soothing a young child and is commonly used at times of stress.

He also stuck his foot out at an angle during his interview, pointing it away from the interviewer in a sure sign that he didn’t want to be there and was ready to move off at any moment.

…and then a step to the right…

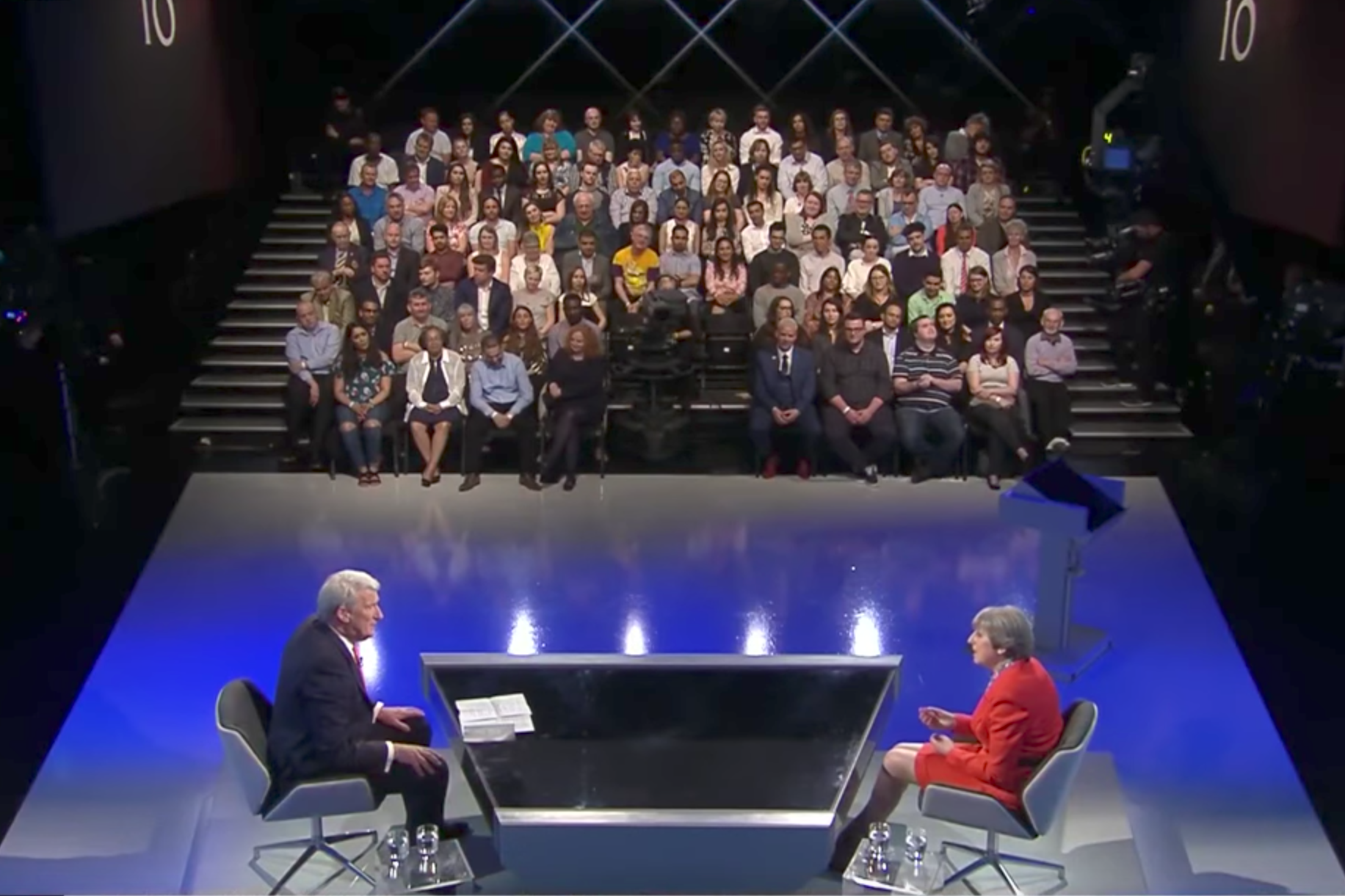

Theresa May, despite her political experience, was also nervous. At the start of her audience question session she could be seen breathing once every two seconds. If she’d continued with that breathing pattern, she would have found herself seriously hyperventilating. Luckily for her, she got it under control fairly swiftly.

Mrs May smiled more than Mr Corbyn, which gave the impression that she was warmer, but sometimes it felt like the smile of a clown: painted on to hide an underlying discomfort.

She also had a habit of tilting her head. Perhaps she did this as a listening pose, but it had the effect of making her look like she has a neck problem, which diminished her stage presence.

Theresa May tends to come across as strong and authoritative. This is partly to do with her pace of speech and her vocal timbre. But on TV, her high heels prevented her from breathing properly and projecting her voice effectively. This exaggerated her vocal strain, which didn’t do her any favours.

Like Jeremy Corbyn, she also stood with her weight on one foot – a bad plan for anyone who wants to come across with true gravitas, as it means that part of your brain has to focus on balance, and this reduces the ability to focus on communication. (Is it purely chance that Mrs May favours her right foot while Mr Corbyn favours his left foot?)

Finally, although this isn’t strictly related to body language, I don’t think senior politicians should wear short skirts. Who wants to see the Prime Minister’s thighs when she sits down for an interview? This has nothing to do with prudishness or feminism but everything to do with cultural and religious sensitivities – not mine, but those of many in our very multi-cultural society. We have never seen Angela Merkel in a short skirt. I think she could give Theresa May a few lessons in political dress etiquette.

So who will win?

Right from the start, even some of the most hardened Labour supporters have thought this election a done deal – even though Labour are closing the gap on the Conservatives and a poll today shows we might even end up with a hung parliament.

As an unbiased, floating voter at this stage, I think Mrs May’s authority will sway the public, regardless of her politics. She comes across as much more powerful and for the most part she engenders respect with her physicality and her voice.

Unfortunately for Labour, Jeremy Corbyn doesn’t, and I suspect that this is Labour’s downfall – not just choosing a leader whose policies cause so much controversy, even within the party, but choosing someone who lacks the gravitas and executive presence that other people look up to and admire.

(With thanks to Sky TV for the screenshots of the TV programme, and to Chatham House for the use of Jeremy Corbyn’s photo.)